A Chocolate and Culinary Celebration in the Birthplace of Cocoa

Posted by in Eat & Drink | South & Central America | UncategorizedArticle appeared in Taste & Travel International magazine

It’s the cusp of rainy season, in Belize’s rainiest and remotest southern region, Toledo. The keel-billed toucan sits on his painted perch high up in the rainforest canopy of the town’s clock tower mural. The national bird of Belize knows the tropics will soon be at their most tropical. Punta Gorda, Fat Point in Spanish, is a border town, known to backpackers as a port where they can catch the ferry to Guatemala. The last place we are expecting chocolate, candlelight, food and wine. The mix of Creole, Maya and Garifuna cultures, with influences from the Caribbean, Mexico, Africa, Guatemala, China and East India, make it the perfect place for a festival.

The stars in the clear skies blink in sync with the tiny lights that trace the inner walls of the rooftop terrace of the University of Belize as the Wine & Chocolate evening, which kicks off the 4th Annual Cacaofest, begins. The Cacaofest, a celebration of chocolate-making and all things Belizean, is officially underway. A flutist plays traditional music. Tourists, ex-pats and Belizeans from all over the country are streaming up the stairs to the sold-out event. Chocolate tasting tables arranged by Belize’s artisanal chocolate-makers (Cotton Tree, Goss, Cyrila’s and Kakaw), a selection of Belizean wines and a fragrant, culturally-inspired buffet, based on a sampling of Creole, Maya and Garifuna dishes, await the crowd.

Cocoa, cacao or kakaw?

The tradition of chocolate-making in Belize traces its origins back about 1,500 years to the Mayans. Toledo is an ancient centre of Mayan culture and has the largest concentration of Mayan villages in Belize. A number of important ruins are nearby, including Lubaantun, Nim Li Punit, and Uxbenka.  It was the Maya who discovered how to transform cocoa beans into chocolate, and the word cocoa is derived from the Mayan word kakaw, pronounced “ka-ka-wa”, written “cacao” in Belize today. Mayan kings drank chocolate as a sacred beverage and an aphrodisiac. They traded cacao beans as currency and even taxed the brown bean. Now, after over 1,500 years, during which the Mayan civilization collapsed, the ancestors of those Mayan cacao farmers are earning their livelihood from the crop. The farmers export their beans through the Toledo Cacao Growers Association (TCGA), founded in 1984 and based in Punta Gorda, a not-for-profit co-operative of over a thousand small farms. And chocolate is, of course, still a currency for cultural exchange.

It was the Maya who discovered how to transform cocoa beans into chocolate, and the word cocoa is derived from the Mayan word kakaw, pronounced “ka-ka-wa”, written “cacao” in Belize today. Mayan kings drank chocolate as a sacred beverage and an aphrodisiac. They traded cacao beans as currency and even taxed the brown bean. Now, after over 1,500 years, during which the Mayan civilization collapsed, the ancestors of those Mayan cacao farmers are earning their livelihood from the crop. The farmers export their beans through the Toledo Cacao Growers Association (TCGA), founded in 1984 and based in Punta Gorda, a not-for-profit co-operative of over a thousand small farms. And chocolate is, of course, still a currency for cultural exchange.

“This chocolate is made with allspice and wild vanilla,” encourages the woman at Cyrila’s, from the Mayan village of San Felipe. I almost inhale my truffle, which is dripping with rich Belizean cream. The smooth, organic chocolate tastes intense and ethereal. Chocolate cashew cups from Goss in Seine Bight must be tried with the cashew wine. The wine is produced not from the nut, but from the fermented juice of its fruit, called a cashew apple. It is musky, nutty, sweet, mild and low in alcohol.

Blackberry wine is made from very ripe fruit and can vary in sweetness. Cyrila’s makes a cacao wine which tastes like sherry, with honey and chocolate notes. Belizeans can turn just about anything into wine (and also fruit brandy or rum) – from local fruits, which include cocoa, blackberry, mango, pineapple, apple, grapefruit, starfruit, sea grapes, cashew, guava, craboo and also from pumpkin, rice, ginger & cassava and even from herbs, flowers and cider bark.

“We love the smell. We love the taste. We love the glorious chemical, whole-body, euphoric reaction,” Jo and Chris Beaumont, from Kakaw Chocolate on Ambergris Caye, enthuse on Kakaw’s site. Kakaw is serving liquid chocolate into which we dip wedges of mango, nutty pineapple and buttery papaya–a velvety organic fruit and chocolate fondue. We talk about tasting notes in chocolate, such as citrus, blackberries, caramel and cashew nuts. In Belizean chocolate these aren’t added ingredients, but flavors brought out during cacao’s long transformation from bean to bar. Apparently, there can be over 600 natural flavors hidden in a single piece of chocolate.

“We always know which farm our beans are from,” says Juli Puryear, who runs Cotton Tree Chocolate. Cacao beans only grow in the south, which gets the most rainfall and Cotton Tree sources all its beans from the farms and Mayan villages which surround Punta Gorda. Cotton Tree makes not just single-origin chocolate, from the beans of one region, but each batch starts with the organically-grown beans from a single day’s harvest and a single farmer. Chocolate made in Belize comes with a best-before date, a batch and bar number and each bar tastes slightly different.

The chefs of the region incorporate chocolate into traditional savoury dishes and we sample a few. I dip fresh shrimp into a Belizean mole, a traditionally Mexican sauce made with chocolate, chili peppers, onion, garlic, tomato, and cilantro and served with Creole rice and beans, made from red pinto beans and mixed with rice and coconut milk (“rice & beans” cooked together is a different dish to “beans & rice” which are served separately). I try the cracker-like cassava bread, a Garifuna tradition, which comes with hummus. Mayan corn tamales, with meat and cheese fillings, are served steamed and wrapped with a plantain leaf.

The Garifuna and Cassava Bread-making

Cassava bread-making is a Garifuna culinary tradition and the rituals of making cassava bread connect the Garifuna to their ancestors. The Garifuna are descendants of native Carib and Arawak peoples from Central America who intermixed with African slaves. Cassava (ereba) is a vegetable whose gnarled root comes from a shrub and it is a staple, the potato of Garifuna cooking. The unearthed root only lasts 48 hours, but the bread keeps for several years. Cassava bread is labour-intensive. The skin is peeled off the root using a sharp knife. The root is pulverized using a wooden

Cassava bread-making is a Garifuna culinary tradition and the rituals of making cassava bread connect the Garifuna to their ancestors. The Garifuna are descendants of native Carib and Arawak peoples from Central America who intermixed with African slaves. Cassava (ereba) is a vegetable whose gnarled root comes from a shrub and it is a staple, the potato of Garifuna cooking. The unearthed root only lasts 48 hours, but the bread keeps for several years. Cassava bread is labour-intensive. The skin is peeled off the root using a sharp knife. The root is pulverized using a wooden

grating board (an egi.) The cassava is then stuffed into a long, woven basket (a ruguma), which is hung from a tree overnight to strain the cassava and to ensure all the juice is extracted, as the juice contains a naturally-occurring cyanide, which is poisonous. Once dried, the cassava is sieved through flat, rounded baskets (hibise), to form a fine flour. The flour is spread over a large, hot iron griddle (comal), to toast. The bread is kept flat with a wooden tool (garagu). The finished bread is crisp and cracker-like.

“It takes three days to make a single batch of chocolate,” Juli laughs. “We call it The Very Slow Food Movement.” Conditions for chocolate-making aren’t perfect, as the temperature hovers around the 30-degree mark. Heat doesn’t deter chocolate-lovers. It’s high noon and a line-up is forming outside Cotton Tree. The cultural hodgepodge reflects the ethnic diversity of Belize –teenagers who are Creole (African and British) speak English and “kriol,” a local patois based on English, Mestizo (Mayan and Spanish–speak Spanish, English and one or two Mayan languages), East Indian and Garifuna (African and Carib, speak English and “Garinagu”), a Mennonite farmer, a Chinese business owner, a British ex-pat and a few backpackers.

Juli, who runs Wilma Wonka’s Espresso Café & Cotton Tree Chocolate from a single-room building, with three employees, produces about 20,000 chocolate bars a year. Wilma Wonka’s self-titled “Chocolate Center of the Universe” produces “bean to bar” chocolate, with 100% Belizean ingredients. The sign for Wilma Wonka’s is in line with the tradition of funky, hand-painted signs all over Belize, which give the towns the sleepy look of another era.

“Our methods are a little unconventional,” Juli says, “but they work.” I watch her assistant use a battery-operated power drill to grind the beans into nibs. A hand-held blow dryer is used to remove the shells from the roasted beans. “The conch is the heart of the operation,” says Juli. She originally fashioned a make-shift conch, which refines the chocolate and cuts the sharp taste of cacao, out of a big green bowl used for making Indian dahl. “The first time we tried it, the top came off and the walls were covered in chocolate.” They now have a new conch, imported from the U.S. The end result of this mostly manual process is a thriving business which provides jobs to local workers, sustains cacao farmers and pays them fairly for their beans.

chocolate and cuts the sharp taste of cacao, out of a big green bowl used for making Indian dahl. “The first time we tried it, the top came off and the walls were covered in chocolate.” They now have a new conch, imported from the U.S. The end result of this mostly manual process is a thriving business which provides jobs to local workers, sustains cacao farmers and pays them fairly for their beans.

Of course, the process begins with the Mayan farmer who produces the large, pinkish-red cacao pod. On Cacaofest weekend, buses head to the organic cacao orchards at Cyrila Cho’s farm. The tour includes a Mayan lunch, a spicy caldo (chicken soup) served with hand-made corn tortillas cooked over an open fire and kaku, a chocolate drink made from beans grown on the Cho farm. Cacaofest weekend finishes on a musical note, with a concert at Lubaantun (“Place of the Fallen Stones,”) in the foothills of the Maya mountains. The ancient stones, eroded by foot traffic of the centuries, provide an exotic, if uneven dance floor. Only the setting sun brings the festival to a close.

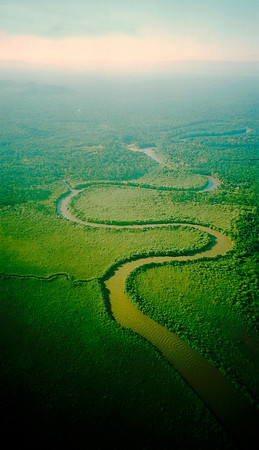

On the one-hour flight from Punta Gorda to Belize City en route home, we fly over lush, broccoli rainforest, the soft mounds of the Mayan mountains rising and falling. I hope to catch a final glimpse of a hidden temple, but all I see is a muddy snake of a river and the sun-drenched thread of the Southern Highway tracing the shoreline and veering inland. On the coast, white waves crash over briny mangrove. A distant cruise ship looks like an iceberg. Bright green islands pop up out of the marsh, foam cut-outs from a school project. I strain to get a view of the wispy threads of distant cayes. The setting sun hits the swampland and the plane is reflected in a dozen orange mirrors. I think how, with every visit, I learn a bit more about this tiny but diverse country. Like the tasting notes in its smooth, organic chocolate, Belize is a complex, harmonious blend of culture, food and language that always makes it worth one more visit.

If you go:

The 2011 Toledo Cacaofest is from May 20-22nd. Visit www.toledochocolate.com and http://www.travelbelize.org/.

Accommodation:

Coral House Inn www.coralhouseinn.com

Cotton Tree Lodge www.cottontreelodge.com

Blue Belize Guest House www.bluebelize.com

Seafront Inn www.seafrontinn.com

Hickatee Cottages www.hickatee.com

Media

View Print Version of Article

View my Blog post on Savour Belize here

Map

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 Both comments and pings are currently closed.